Headless WordPress has been a buzzword in the web development world in recent years. You hear that it would be “the future” and that it offers all kinds of benefits. But as a sober technical strategist I ask myself: when is headless WordPress truly a smart, rational choice for your project, and when does it mainly add unnecessary complexity? In this blog post I explain what headless WordPress actually is, in which situations it can be an advantage and in which cases you’re better off sticking with traditional (classic) WordPress. We look at the definitions and terms, legitimate use cases, why headless is often overkill for standard sites, alternative solutions, the operational reality of a headless setup, and we finish with a practical decision checklist.

Let’s dive into the subject without hype or vendor promotion and form an honest answer to the central question.

Definition & scope: What is headless WordPress (and what isn’t it)?

Headless WordPress means, at its core, that you use WordPress only for the management part (the back-end) of your site, and not for the front-end presentation. In other words: the “head” (the front-end) is removed. Content is managed in WordPress, but the presentation happens through a separate application or website that fetches the data via an API.

In a traditional WordPress site, back-end and front-end are tightly connected: you enter content via the WP dashboard and a theme makes sure that content is shown to visitors. In a headless (decoupled) setup those two are fully separated. WordPress functions purely as a content management system and exposes the content via a web API (e.g. REST or GraphQL) to external applications. Those external “clients” can be anything: a custom website built in React or Vue, a mobile app, a digital kiosk, you name it. In that case WordPress no longer serves HTML pages to the visitor; the external front-end application does that.

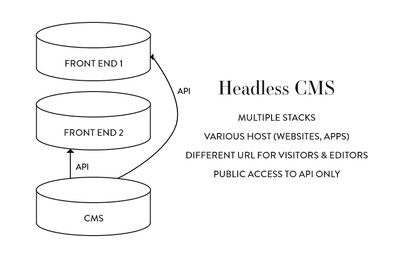

Figure: Schematic view of a headless CMS. Content sits in WordPress (back-end) and is shared via an API with different front-ends (for example a website and a mobile app). The “head” is missing – WordPress only handles management and storage of content, while external clients take over presentation.

What it is not: Headless WordPress is not a special version or plugin of WordPress, but an architectural choice. Since WordPress 4.7 a JSON REST API has been a standard part of WordPress Core. So you don’t need to install a separate “headless CMS” package – it’s the same WordPress, you just use it in a different way. The term headless purely refers to the absence of a coupled front-end. It’s also not the case that headless automatically means better content management or easier editing – the WordPress back-end remains largely the same for content editors. What you do lose are certain front-end bound features (think theme rendering, widgets, shortcodes that render directly, etc.).

Decoupled vs headless: in practice, headless and decoupled are often used interchangeably. Both terms point to the same decoupling of front-end and back-end. Sometimes people mean a slightly broader category with decoupled, where the front-end can still be partially rendered by the CMS. But in general for WordPress you can assume that decoupled simply refers to the principle of headless (a decoupled architecture).

Hybrid (hybrid) WordPress: This is a middle ground where you partly keep the traditional approach and partly work headless. You could, for example, extend an existing WordPress site with a separate front-end component. In practice we often see such hybrid setups: the base of the site stays traditional WordPress for the regular pages, but a specific part (for example a job search module or interactive tool) is built as a separate React/Vue component that fetches content via the API. Such a hybrid approach gives you headless flexibility where you need it, while the rest of the site keeps running the familiar way. Another interpretation of hybrid is a combination of headless with statically generated pages (static site generation). You then build a front-end that uses WordPress data, but pre-renders as much content as possible to static HTML to increase speed and security – while WordPress stays in the background for management. These kinds of hybrid architectures try to take the best of both worlds, but they obviously bring their own complexity as well (more on that later).

Legitimate use cases for headless WordPress

When can headless WordPress really add value? There are a few scenarios in which this architecture is a rational choice:

- Multichannel content and omnichannel publishing: This is perhaps the most important reason to choose headless. If you want to offer your content across multiple channels at the same time – think a website, a mobile app, a customer portal, maybe even info kiosks in stores or posts on social media – then it helps to have one central content hub. Headless WordPress makes that possible: you enter the content once (in WordPress), and via the API that content can be sent to multiple platforms and devices at the same time. Imagine a retailer with hundreds of stores who wants to show vacancies or product information both on the corporate website and in a mobile app and internal kiosks – one WordPress backend can serve all channels. These omnichannel scenarios are where headless really excels.

- Complex front-end requirements and web applications: Sometimes you want a very interactive or highly tailored user experience that is hard to achieve with a standard WordPress theme. Think of a web application with lots of client-side interactivity, real-time updates, complex search filters, or a personalized environment for users. In such a case headless WordPress can be a solution: developers have full freedom to use modern front-end technologies (React, Vue, Angular, etc.) and build exactly the UI that’s needed, without being limited by WordPress templating or PHP. WordPress then functions purely as a content database. For example: you build an extensive single-page application for a web service, but use WordPress in the background so content managers can manage the content via a familiar CMS. Also if you want one backend for multiple applications – for example you use the same data for both your website and a mobile app – a headless (decoupled) architecture is very suitable.

- Scalability and performance at high scale: A well-configured traditional WordPress site can handle a lot, but there are situations where extreme performance demands or scale play a role. With headless you can scale the front-end separately from the back-end; for example you can use a static site generator or server-side rendering to serve super-fast pages via a CDN, while WordPress runs in the background on its own server. For websites with tens of thousands of content items, or very heavy interactive components, this can be beneficial. For example: a job board with >5000 vacancies and complex filters that needs to load in milliseconds – a Next.js front-end with server-side rendering might handle that faster than WordPress with PHP templates. One caveat: always ask yourself whether performance is really your bottleneck. In most cases where a WordPress site is “slow,” the cause is poor caching, weak hosting, or too many plugins, not WordPress itself. With good optimization you can often go from 5-second load time to ~1 second without going headless. So use headless only if, after optimal caching/hosting, you’re still hitting the limits of WordPress.

- Security as a priority: A commonly mentioned advantage is that with a headless setup the WordPress backend is less exposed to the outside world. The public website is a separate application (or even a static file) that fetches data via the API. In theory this gives a smaller attack surface – malicious actors can’t directly reach your WP login page or database through the site. A single content update does appear across all channels, but the WordPress environment itself is separate from the front-end the user sees, which can be safer. That said: this does not mean you suddenly have no security concerns. Your WordPress still needs to be up to date and secured, and your new front-end can bring its own vulnerabilities. Still, this isolated character can be an advantage in some architectures (such as statically generated front-ends): even with infrastructure outages or attacks on one front-end, other channels may remain available. Security can therefore be a (secondary) argument in environments where this is crucial, as long as you set up the whole stack properly.

Conditions: The use cases above sound attractive, but in practice they also place demands on your organization. You need enough technical talent and budget to realize and maintain a headless project. It’s not something you “do on the side” without dedicated development capacity. You also have to be willing to carry extra complexity across the entire lifecycle of the site (think continuous updates to the front-end framework, API changes, etc.). In an enterprise with a full development team and a long-term vision, that can be fine. But for an average SME or a digital agency without a large internal dev team, this is a serious hurdle. In other words: headless can be rational, but only under the right conditions. If you don’t have those, the downsides quickly outweigh the benefits – which we’ll get into next.

When headless is not a good idea

For many standard websites in the Dutch context, headless WordPress turns out to be mostly overkill. Here are situations and reasons where you’re better off not choosing headless:

- You’re building a marketing website or simple corporate site: For the average company website, landing page, or blog, headless adds little beyond complexity. Such a site usually has a few static pages, a contact form, maybe a news section – all perfectly doable within regular WordPress. A traditional setup is often faster to build and easier to manage. Headless would mean you need to develop and maintain two systems (WP + custom front-end) for functionality that a standard theme or page builder can already provide. You also often run into SEO challenges when you go headless on marketing sites. A standard WordPress site is naturally SEO-friendly (think SEO plugins, metadata, sitemaps, etc.), whereas a headless front-end has to re-implement all of that. Without server-side rendering or extra development work, single-page front-ends can be harder to index. You then have to handle things like meta tags, sitemap XML, RSS feeds, link previews, etc. yourself – you no longer get them “for free” from WordPress. For a pure content site, that’s rarely worth it.

- You don’t have dedicated developers (and don’t actually want to need them): This is perhaps the biggest reason not to go headless. In a traditional WordPress scenario, a marketing or content team can create pages, adjust text, change a call-to-action color, you name it. With headless, that freedom largely disappears: every change to the front-end presentation requires code changes, and therefore a developer. Your team loses agility with headless, because for every change – from a new button to a small layout tweak – a developer has to be involved. This creates dependency and a bottleneck you don’t want in a small team. If your organization doesn’t have the capacity to keep developers on standby for content changes, you’ll get massively frustrated. Real-world example: a marketer who can build a new landing page in 30 minutes in classic WordPress would first need to ask a developer to build or adjust a component in a headless setup, which can take hours to days. Quickly A/B test a different headline or image? Instead of “click and done,” it now gets stuck in the development sprint. In short: no internal dev team available = don’t start headless.

- You want to iterate and experiment quickly: This is related to the previous point. Companies that run lots of marketing campaigns, publish new content weekly, or do a lot of A/B testing thrive in a system that’s easy to adjust quickly. WordPress in its classic form is very suitable for this – content teams can launch things fast. Headless introduces delay in this process. Your “time to market” for small changes becomes longer because it runs through developers. If you’re in an environment where flexibility and fast iteration matter more than absolute technical perfection, headless is usually a bad choice. Think campaign sites, temporary promotions, or content marketing: in those cases you want less technical overhead, not more.

- Your resources and budget are limited: Headless asks more on all fronts: more development time, more infrastructure (you often run double hosting – the WordPress backend and separate hosting for the front-end), and structurally more maintenance work. If you haven’t explicitly reserved resources for that, you create a recipe for technical debt that keeps growing. We often see organizations enthusiastically build a headless project, but after launch they don’t have the capacity to keep it up. Result: the front-end part isn’t updated and becomes outdated, security patches are missed, or people hesitate to update WordPress because the custom integration might break. This increased maintenance load should not be underestimated. For a normal business website it’s simply not cost-effective to carry the costs and effort of two separate systems if one system can do the job.

- E-commerce (WooCommerce) without extreme requirements: The headless paradigm is sometimes applied to WooCommerce stores, but for most webshops (<– enterprise level) this is not recommended. WooCommerce is tightly intertwined with WordPress and is powerful precisely because it handles a lot out of the box: from product listings to cart and checkout. If you go headless, you have to rebuild all of that custom in your front-end application – a huge investment that only makes sense if you want to build a unique, highly complex shopping experience and have the scale to justify it. You also run into plug-in compatibility: many WooCommerce extensions and payment plugins assume they run inside a WordPress environment and won’t just work via an API. So you limit your tool choices or have to find alternatives. Again, development and hosting become more expensive because of two separate systems. Unless you have an enterprise use case where standard WooCommerce really falls short (e.g. headless for better performance with huge catalogs, or a very custom UI requirement), headless WooCommerce is usually overkill. In the Dutch context, where many SME webshops run fine on WooCommerce, the extra complexity almost never outweighs the marginal gains.

- “Latest technology!” is the main argument: A warning is in order for situations where the team wants headless mainly “because it’s more modern” or “because developer X likes working with React.” Choosing technology based on hype or developer preference instead of business need is dangerous. It happens that developers find traditional WordPress boring and would rather use a fancy front-end stack. But if that’s the only argument, you’re probably rationalizing in the wrong direction. Use headless because it delivers value to the business, not because it looks good on someone’s CV. In many cases, saying no to the hype is actually a sign of maturity in technical choices – we’ll return to that in the conclusion.

In summary: headless WordPress is not a miracle cure that benefits every site. Especially for standard content sites, marketing-driven websites and typical WooCommerce shops it often adds more complexity than value. You lose functionality (many WordPress plugins don’t work headless out of the box), you have to build more yourself (especially around SEO, navigation, search functionality, forms, etc.), and your organization has to be ready to carry that overhead. In most cases, a well-configured classic WordPress setup can achieve many of the same goals without the downsides outlined above.

Comparison with alternatives: classic, partial headless & other architectures

How does a headless WordPress approach compare to the alternatives? Let’s look at the trade-offs of a few approaches, without falling into black-and-white thinking:

Traditional WordPress (monolithic CMS)

This is the “standard” where WordPress both manages the content and renders the front-end. The biggest advantage is simplicity: one system to manage, and you get a lot of functionality out of the box. Things like user management, forms, SEO tools, caching plugins, themes – it’s all available and often can be enabled with a few clicks. You need relatively little technical knowledge to run or adjust a site. WordPress is also widely supported: almost every hosting provider can run it and there is a huge community and ecosystem. This makes it a cost-effective choice for many projects. Your development costs are lower and future changes can often be made without a developer.

The downside of classic WordPress is that you’re tied to a PHP- and theme-based front-end. That can limit ultra-advanced UI/UX ambitions – you stay within the boundaries of what themes and plugins can do, or you have to dive deep into code to do custom PHP work. Content and presentation are also coupled, which makes it harder to use the same content on other platforms (there are solutions, but it’s not the default). Performance requires attention: standard WordPress generates pages dynamically on every request, so you need caching and optimization to get truly fast load times. In short, traditional WordPress scores high on usability and development speed. It’s often the most pragmatic choice when you want to build a good website with minimal resources. For many companies, the “old trusted” WordPress is for a reason the wisest choice. You’re fully in control, you have a flexible page structure for both marketers and developers (thanks to the many available plugins, themes and API integrations), and you’re not locked into expensive custom trajectories.

Fully headless CMS (100% decoupled)

If you choose fully headless (whether WordPress as the backend or another headless CMS solution), you invest in maximum flexibility and future possibilities. You can use any modern frontend technology, connect multiple front-ends to the same data, and you’re not limited by the legacy of a platform. This offers the chance of excellent performance (for example through static site generation or specialized front-end optimizations) and ultra-modern user experiences. You can also theoretically replace part of your stack more easily – because the front-end and back-end are separated, you can rebuild the front-end without migrating the whole CMS (or vice versa). You also avoid vendor lock-in to a specific theme or plugin supplier, because everything is custom and under your control.

But that freedom comes at a price: complexity and responsibility. You now have to build and maintain two (or more) systems instead of one. Development takes significantly more time and requires knowledge of multiple technologies (WordPress/PHP and, for example, React/Node for the front-end). This translates directly into higher development costs and often more expensive hosting setups. You lose part of WordPress’ “free” functionality: many plugins don’t work automatically in a headless context, so things like forms, search functions, image galleries, and so on have to be re-implemented or built through workarounds. SEO and content preview also require extra work – the standard WordPress preview no longer works out of the box, and you’ll have to generate static pages or add server-side rendering to keep search engines happy. In governance terms: control shifts to developers instead of content editors. For organizations this means you need an experienced (online) marketing team that can handle the new workflow, and a development team that is constantly on standby. Fully headless is the other extreme from traditional WP: technically very powerful and flexible, but also a heavier and more expensive route where you must consciously accept the trade-offs.

Hybrid or partially headless approach

The hybrid approach tries to strike a middle ground. Instead of converting everything to headless, you look at where it’s truly needed and apply headless there, while keeping the rest traditional. As mentioned earlier, this could mean that you keep your main site running in WordPress (including a theme for standard pages and the blog), but decouple a specific module. For example: you build a React component for the product catalog or job search that pulls data via the REST API, because that section benefits from faster filtering or a SPA-like experience. The rest – the “about us” pages, news posts, etc. – you still render via the WordPress theme. This way you keep the usability for content editors on most of the site, and you invest in headless only where it’s needed.

Another version of hybrid is to use WordPress headless combined with static generation: you use a modern front-end framework (e.g. Next.js) that fetches content via the WP API, but you periodically build static HTML pages that are super fast and safe to serve. This is also called Jamstack or “static headless.” WordPress still functions as the editor tool, but the live site is deployed as static on a CDN. You can combine this with client-side interactivity for dynamic parts.

The benefits of a hybrid approach are obvious: you only pay the complex solution for the parts that truly require it, and you keep the rest nice and simple. Your editor team barely notices anything for the traditional part, and your developers can still experiment with modern techniques on a controlled slice of the site. You get targeted performance wins on the critical parts without rebuilding everything. You can also migrate step by step: today make one component headless, the rest later (or never) – less risk than a big-bang switch. Of course hybrid work also brings complexity: you have to make two systems talk to each other for the hybrid parts and ensure it feels seamless for the user. You also still have two codebases (even if not for the entire site). It requires knowledge of both WordPress and the front-end stack. Still, in practice this is often a pragmatic way to benefit from headless where needed without carrying all the downsides everywhere. Many digital agencies therefore choose partial decoupling: “headless for X, traditional for Y.” Think of a site where the jobs section is headless for better search functionality and performance, while the news blog and regular pages run through the WP theme. These hybrid models combine flexibility, performance and security (via static pages, for example) while retaining a large part of WordPress’ convenience. The trade-off is more fine-grained: you increase complexity only where you also gain the most.

Operational reality: what does headless mean for maintenance, security, debugging, transferability and costs?

So far we’ve looked at things conceptually, but how does a headless WordPress choice play out in day-to-day practice after launch? It’s important to be realistic here, because the pretty promises can turn into headaches if you can’t handle the operational consequences.

More maintenance and technical complexity

A traditional WordPress site needs to be kept up to date (core updates, plugin updates, occasionally bumping the PHP version, etc.). With a headless setup a whole extra package comes on top: you now also have a custom front-end application with its own dependencies. Think JavaScript frameworks and libraries that need regular updates (for new features or security fixes). So you need to patch and update twice – both WordPress and the front-end. This requires a solid deploy and test process: updates on the backend can change the API or influence plugin output, which impacts your front-end rendering. Conversely, changes in front-end code can have unforeseen effects on how data is displayed (or errors if the API returns something your code doesn’t expect).

There are also more moving parts that can break. Where in a normal WP site you mainly look at web server + database, you now have, for example, a separate Node.js server or build step, API calls between systems, and so on. Debugging issues becomes more complex: if “something doesn’t work,” you have to determine whether the issue is in the WordPress backend (e.g. a plugin returning weird data), in the API layer (authentication, permissions issues) or in the front-end code (bug in a React component). For non-developers this is nearly impossible to analyze. You’re therefore heavily dependent on technical people to solve problems.

Maintenance therefore requires more discipline and planning. You can’t just set WordPress 6.x to “auto update” without checking whether your custom front-end can still handle it. We often see organizations drop the ball here, which slowly creates technical debt. For example: people hesitate to run core or plugin updates because they fear breaking the headless integration, so they remain on old versions – with security risks as a result. Emplear put it well: without enough resources, headless becomes technical debt that keeps growing. You must be willing to invest time and money structurally in maintenance to keep the system healthy.

Dependence on specialists and transferability

We already hinted at it: a headless site makes your organization more dependent on developers for both big and small changes. This also affects transferability and continuity. Suppose you hire an external agency that builds a hip headless website for you. What happens two years later if you want to work with another party, or if that specific developer leaves? Finding a replacement can be harder, because you now have a very custom stack. Traditional WordPress developers are abundant, but someone who understands both WordPress and framework X and wants to take over your specific implementation is rarer (and more expensive). The community around headless WordPress is growing but smaller than the regular WP community. This means fewer off-the-shelf solutions on forums, fewer developers who can “jump right in,” and potentially more dependence on the original builders.

For internal content editors and marketers the new workflow can also feel like a step backwards. Things that used to be easy (e.g. drag-and-drop a new page layout with a page builder) suddenly become development tasks in a headless environment. The risk is that marketers get frustrated because every request ends up in the development backlog queue. Knowledge transfer within the team also becomes harder: a new marketing team member can’t just get “quick WordPress training” and then do everything themselves, because the site doesn’t behave like standard WordPress.

Transferability of the website itself (e.g. moving to different hosting or another party) also becomes more complex. A traditional WP site can be migrated or handed over relatively easily; a headless solution consists of multiple components you all have to keep running. For example, you have WordPress hosting for the backend and a Vercel/Netlify (or your own server) for the front-end application. Both have to be configured correctly during a move. Your DevOps/system administration effort is therefore greater.

Security and updates in practice

Earlier we mentioned that headless architecture can have some security advantages (your WP is less directly exposed). In practice, however, this doesn’t mean you can lean back. You must be doubly alert: both WordPress and the front-end stack need to stay up to date and patched. New security releases for WordPress must still be applied as quickly as possible (as always), but now you also need to watch security advisories for your JavaScript framework, your API authentication mechanism, etc. You also need to ensure that the API endpoints WordPress exposes are properly protected – you don’t want sensitive data to be publicly accessible via the API. Access control and verification play a bigger role. Many of these things are solvable (and sometimes even better managed by decoupling), but they do require the right expertise in-house.

Ironically, the benefit of “safer because the database isn’t directly reachable” can be undermined if your front-end code contains vulnerabilities (think XSS, or a leak in an NPM package). So your attack surface shifts, but it doesn’t disappear. Your DevOps/infrastructure approach must be set up for this (API rate limiting, CORS policies, token management, etc.). This is generally manageable, but again: extra work compared to standard WordPress hosting that handles a lot for you.

What often goes wrong after launch?

The biggest pitfall I see in practice is that after the initial build, the required support is underestimated. During the project everyone (agency and client) is enthusiastic about the shiny new headless site. Then the site goes live and normal business has to continue. Now new content wishes or marketing opportunities arise, but every change has to be scheduled with development. If there’s no budget or contract for that, it doesn’t happen – the site doesn’t evolve and slowly loses relevance. Or people start tinkering in WordPress themselves (activating plugins, changing content structure), which can break the front-end integration, again calling for developer intervention.

Another common issue is that performance still disappoints if you don’t continuously tune it. A headless front-end can be blazing fast at first, but if you do a lot of client-side rendering and more and more data gets added, the site can still become slow for visitors – and now you don’t have a simple cache plugin to fix it. It requires continuous monitoring and optimization, more than you might be used to.

Finally, you risk functional regression: new WordPress features or plugin updates that immediately bring benefits on a traditional site have to be manually integrated in headless. Suppose WordPress introduces improved search functionality or a new editor block – in a normal site you can benefit from that right away, but in headless you can’t without custom development. As a result, your site’s functionality can fall behind unless you keep actively developing.

In short, working headless requires a different operational mindset: that of a software product rather than a website. You manage two codebases that work together. If your organization isn’t set up for that kind of software lifecycle (with testing, staging, deployments, bugfix releases, etc.), the reality is often disappointing. A “regular” WordPress site can be managed by a content team with a bit of common sense; a headless site needs ongoing love from engineers.

Decision checklist: headless or not – how do you choose?

For non-technical decision makers (and really everyone) it’s useful to have a few concrete criteria lined up. Below is a simple checklist to determine whether headless WordPress makes sense for your project.

Consider headless WordPress if:

- Your content needs to be distributed across multiple channels or apps (website + mobile app + other platforms) from one source.

- Your organization has dedicated in-house developers or budget to hire a dev team long term.

- You want to modernize in stages: for example gradually replacing parts of a legacy site with a modern front-end without overhauling everything at once.

- Performance at top speed is crucial and your current WordPress site is already fully optimized but still falls short. (This will rarely happen, but for example with very data-heavy applications it can.)

- Your site has an extreme amount of content or interaction, for example tens of thousands of items with complex filtering or real-time functionality, where traditional setups buckle.

- There’s another heavyweight reason a traditional CMS can’t handle well (for example a very unusual front-end user experience that can only be built with custom code).

Stick with classic WordPress (for now) if:

- Your website is primarily a single channel (just a website) and there’s no urgent need to reuse that same content elsewhere.

- Your team mainly consists of content managers and marketers without much technical support. They want to be able to create and adjust pages themselves.

- Flexibility and fast iteration are more important than ultimate custom front-end. You want to publish new content in hours/days, not wait weeks for development.

- Your site has a marketing, information or standard e-commerce goal that can be served well with existing WordPress themes/plugins. With a well-structured theme and some custom work you can already go far – extra complexity adds little here.

- Your budget or timelines don’t allow a continuous development track after launch. A classic WP site can run with less support; headless requires ongoing attention, so no structural budget = don’t do it.

- You’re mainly inclined to choose headless because “it’s a trend” but don’t have a very clear case for why you specifically need that flexibility. In that case: stick with what works, optimize your current site, and wait until a real bottleneck appears.

Of course there are shades of gray, but in general: if you mostly recognize the points in the second list, that confirms a traditional approach is sufficient (or maybe a limited hybrid element here and there). If you recognize many points from the first list, headless may be worth considering – provided your organizational conditions are in order.

Conclusion: when yes, when no, and why “no” is often a mature choice

Headless WordPress isn’t inherently better or worse than traditional WordPress – it’s a different approach with its own trade-offs. In a handful of scenarios (multiple front-ends, very complex applications, extreme scale) it can be a rational, even necessary choice to achieve your goals. Provided you have enough expertise and resources, headless can then offer great possibilities that a monolithic system struggles to provide.

But for most ordinary websites and organizations in the Netherlands, headless is mainly unnecessary complexity. A well-optimized classic WordPress site is fast, flexible, and lets your team work independently without constant dependency. You avoid double maintenance, save costs, and reduce risk. In those cases, choosing not to go headless is a sign of maturity: you pick a proven, simple solution over a hyped technology that doesn’t solve a fitting problem.

My advice is to always evaluate honestly why you would want headless. If the answer is strongly tech-driven (“latest stack!”) instead of business-driven (“we need multichannel”), be critical. If needed, start by getting the maximum out of classic WordPress – cut unnecessary plugins, improve hosting, implement solid caching, test your limits. Only when you truly hit limits that block your goals should you consider alternatives such as headless.

Remember: the “best” technology is not the one that’s most modern or hip, but the one that makes your team most productive and serves your goal most effectively. In many cases that will simply be WordPress in the traditional way. And that’s ok! Dare to say no to unnecessary complexity. Ultimately it’s about what works for your organization. Headless WordPress can be fantastic – at the right time, for the right reason. And in all other cases there’s nothing wrong with leaving the head on WordPress and choosing simplicity. That is often the wisest choice in the long run.